When you do not know where to go or who to turn to, and especially when you do not have the devices or connectivity to get online, you go to the library. The library is a uniquely trusted institution, a community anchor, that not only provides educational and entertainment resources, but also tax assistance, mobile hotspots, telehealth, printing, scanning, faxing, and disaster assistance. During disasters people often face new uncertainties, new problems, and barriers caused by the disaster, and it is difficult to get the answers and resources they need. In our research, we interviewed over 80 librarians and local organizations in small, rural communities in Texas and Florida about their role before, during, and after a disaster. In particular, we asked the librarians to reflect on their experiences with Hurricane Michael in Florida, Hurricane Harvey in Texas, and we asked our Texas librarians to share their experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic.

One key finding from our interviews is that disasters have become the new normal. In addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, cities across the United States have been dealing with multiple, simultaneous disasters for years. Fires, industrial plant explosions, flooding, burst pipes, tornados, winter freezes, and hurricanes were just some of the simultaneous disasters experienced by rural Texas libraries in 2019-2021. These disasters affected library buildings, holdings, and staff, and had larger impacts on the communities these libraries serve. Yet what is the role of the librarian during a disaster? Traditionally, librarianship does not include disaster preparedness and recovery training; yet as a trusted community anchor people turn to libraries when they do not know what to do. Further, libraries remain to serve their communities long after the short-term aid organizations leave and after the funds generated by immediate goodwill run out.

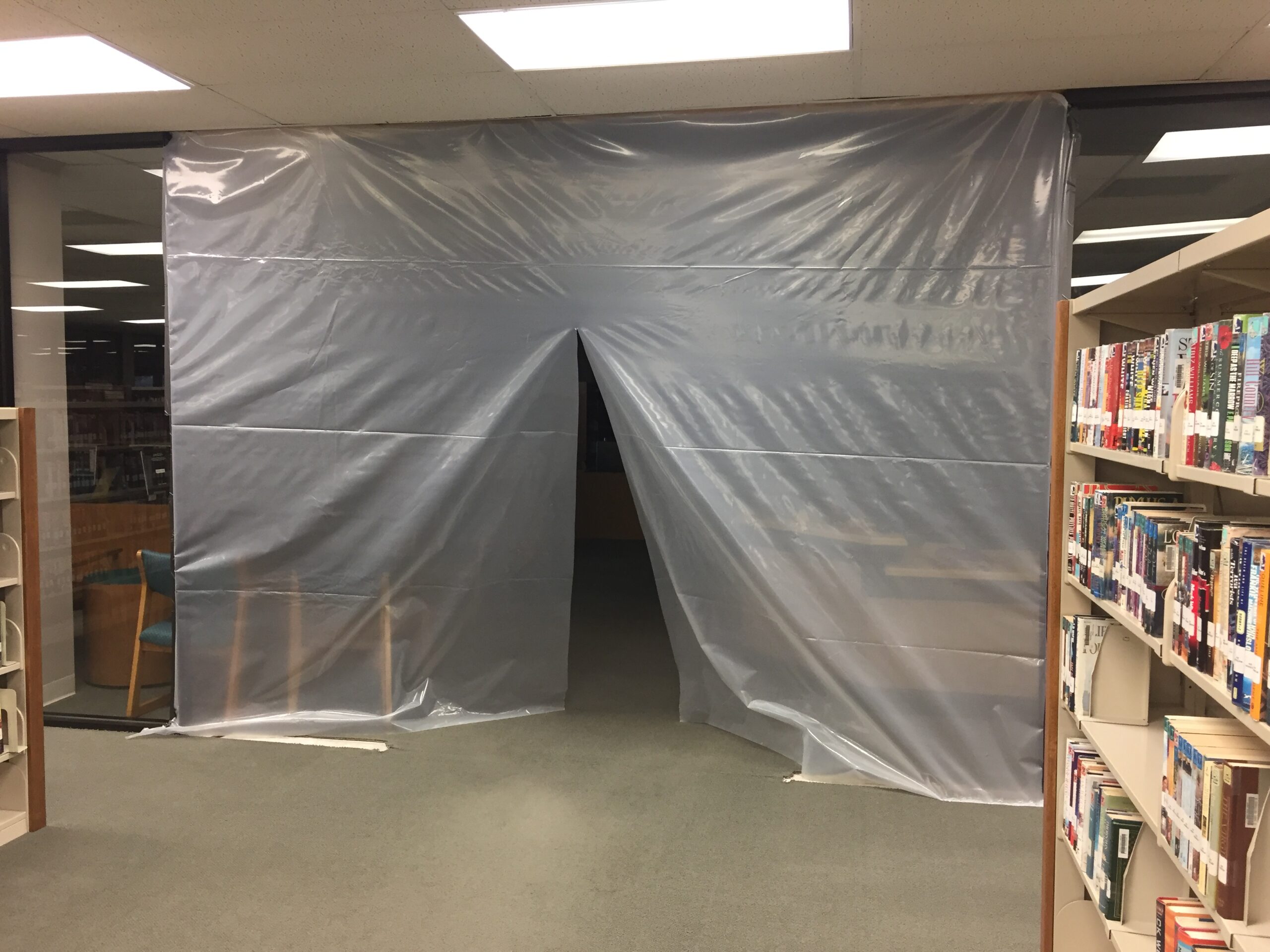

Damage to the Port Neches library after nearby plant explosion

The recovery period of a disaster can go on for years, particularly in rural communities that often lack strong systems of aid and recovery. After Hurricane Harvey, librarians helped relocate displaced individuals who could not return to their homes even 2 years after the hurricane. One librarian in particular sheltered an elderly member of their community on and off for 2 years after Harvey while they transitioned between temporary housing assistance. Although Harvey was catastrophic, rural coastal Texas librarians have been assisting their communities with relocation and housing services for years, one librarian described it as “routine.”

The unique relationship between libraries and their communities has resulted in librarians being on the ‘frontlines’ of disaster response and recovery. However, as traditional notions of librarianship are not explicitly about disaster management oftentimes librarians operate outside of local government and regional disaster plans. Subsequently, librarians fill in the gaps for their local communities that lack access to a disaster network. Librarians also respond to disasters and help communities plan for the library’s role in a disaster. Subsequently, librarians need to advocate for the work they already do to mitigate disasters and their contribution to community resiliency, and local governments need to incorporate libraries into their disaster planning to better account for how people are using libraries when disasters strike.

(Top image: flooding in Port Arthur Texas Library after Hurricane Harvey)