Rural Libraries and Disasters

Investigating resiliency in the digital environmentIntroduction

This research investigates the situations, constraints and opportunities associated with smaller, rural libraries as they cope with disasters. Conceived in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, a devastating hurricane with huge impact on a large swath of the country, our work quickly evolved into something a little broader. As new hurricanes hit the U.S. and as fires, floods, and later the COVID-19 pandemic wracked both urban and rural populations, we began to consider libraries’ roles in the broader circumstances of disasters. Hence, our research goals changed over the course of the grant, primarily in response to the pandemic, but also in response to the growing public recognition of climate change and the types of physical disasters it encourages.

First, while hurricanes striking the Gulf Coast motivated our initial proposal, our fieldwork underscored the repetitive nature of flooding in our target regions; in the meantime, fires were burning communities, winter storms devastated infrastructures, and unexpectedly powerful tornadoes hit. These are framed as ‘crisis events,’ but their growing, repeated presence and impact on communities forced us to broaden some of the ways we were thinking about disasters and to dive into thinking about resilience in more complicated ways. For example, we noted the repeated vulnerability of certain populations.

Second, we added the pandemic crisis to our research effort as another type of disaster, and effectively created research enabling us to compare community and library responses to yet another type of disaster.

This research brings to light the “invisible” and “unwritten” labor and contributions of librarians to disaster preparation, relief, and recovery efforts. Further, by investigating the best practices of these librarians this research helps librarians learn from their peers. Our research is rooted in conceptual issues around crisis response, the communication systems that root libraries in their communities, and finally, the processes that contribute to community resilience as they may bear on libraries.

Our research questions asked:

-

-

- How do small and rural libraries respond to disaster events and how do they interact with their community members?

- How do libraries use information and communication technologies during and after disaster events? and

- What institutional practices contribute to libraries’ resilience during and after disasters even as they contribute to their communities?

-

Damage to the Port Neches library after a nearby plant explosion.

Methods

This research is the result of two grants from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. The first grant was awarded to examine how rural libraries responded to Hurricane Michael in Florida, Hurricane Harvey in Texas. The second grant focused on how the same Texas libraries responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The approach was qualitative, open, semi-structured interviews and focus groups with librarians and a few local aid organizations. Both Texas and Florida share coast along the Gulf of Mexico, through which hurricanes make landfall throughout hurricane season. In Texas, the locations were determined using the Texas Government Land Office (GLO) maps that identified the “Most Impacted Area” using zip codes and county. These sites were then narrowed down to those that fit Texas State Libraries and Archives Commission’s definitions of rural and small libraries. The Texas library sites were located in Aransas, Brazoria, Jefferson, Orange, Refugio, San Jacinto, and San Patricio counties, and a total of 91 phone, virtual, and in-person interviews were conducted with libraries and organizations in these counties.

The Florida sites were selected using a top-down approach, by communicating with partners in state and regional library organizations to identify library systems in rural counties that had been heavily affected by natural disasters, including 2018’s Hurricane Michael. The panhandle region of Florida experienced the worst of Hurricane Michael, and our sites experienced the top wind speeds at 130-156 mile per hour. In subsequent interviews with library directors of the affected counties, they identified the library branches in which we engaged library staff in further exploration of their experiences. The Florida participants represented four county-based library systems in the northwest of the state, also known as the Panhandle. In the region, these four counties, Bay County, Calhoun County, Gulf County, and Liberty County were the most profoundly affected by Hurricane Michael, and we conducted 2 focus groups and 4 in-person interviews.

IMLS approved a second grant to extend this work to look at how the Texas libraries in our hurricane study responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. In August 2020, we began the data collection of Facebook posts from four of our libraries. We collected Facebook posts that were published between March 1, 2020, through August 31, 2020, during what has been retroactively referred to as the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Interviews with librarians began in November 2020 and, due to the nature of the pandemic, interviews with librarians were conducted remotely and continued until June 2021. 17 one-on-one interviews were conducted with the same libraries that we interviewed for the hurricane study.

Flooding in Port Arthur Texas Library after Hurricane Harvey.

Findings

Research Question 1

Major findings regarding how libraries in small or rural communities respond to disasters included a range of strategies that demonstrated how libraries were uniquely responsive to the needs of their communities. We identified three phases of library action: preparation for disasters, coping with the disaster while it unfolds, and then recovery. When the same type of disaster recurs, preparation is feasible (i.e., installing steel shutters capable of withstanding high winds or blasts). During the disasters, librarians self-elected to provide assistance outside of their traditional roles, such as aiding in helicopter rescues and communicating with their patrons about weather conditions and road closures. The recovery activities we document show how libraries can share costly equipment or simply things most people do not have (shop vacs, hotspots) in order to satisfy peoples’ needs shortly after disasters strike.

Individuals’ emotional needs are highly salient in the aftermath of disaster, and librarians became sources of emotional support. Additional training for librarians in this regard would be desirable. Prioritizing these emotional needs of the community supported community resiliency, yet many librarians felt the pressure to deprioritize their own needs and the needs of their staff and volunteers. The same humanitarian spirit that compels librarians to go above and beyond for their communities created conflict when the personal safety of librarians was at risk by providing routine services. This was particularly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic.

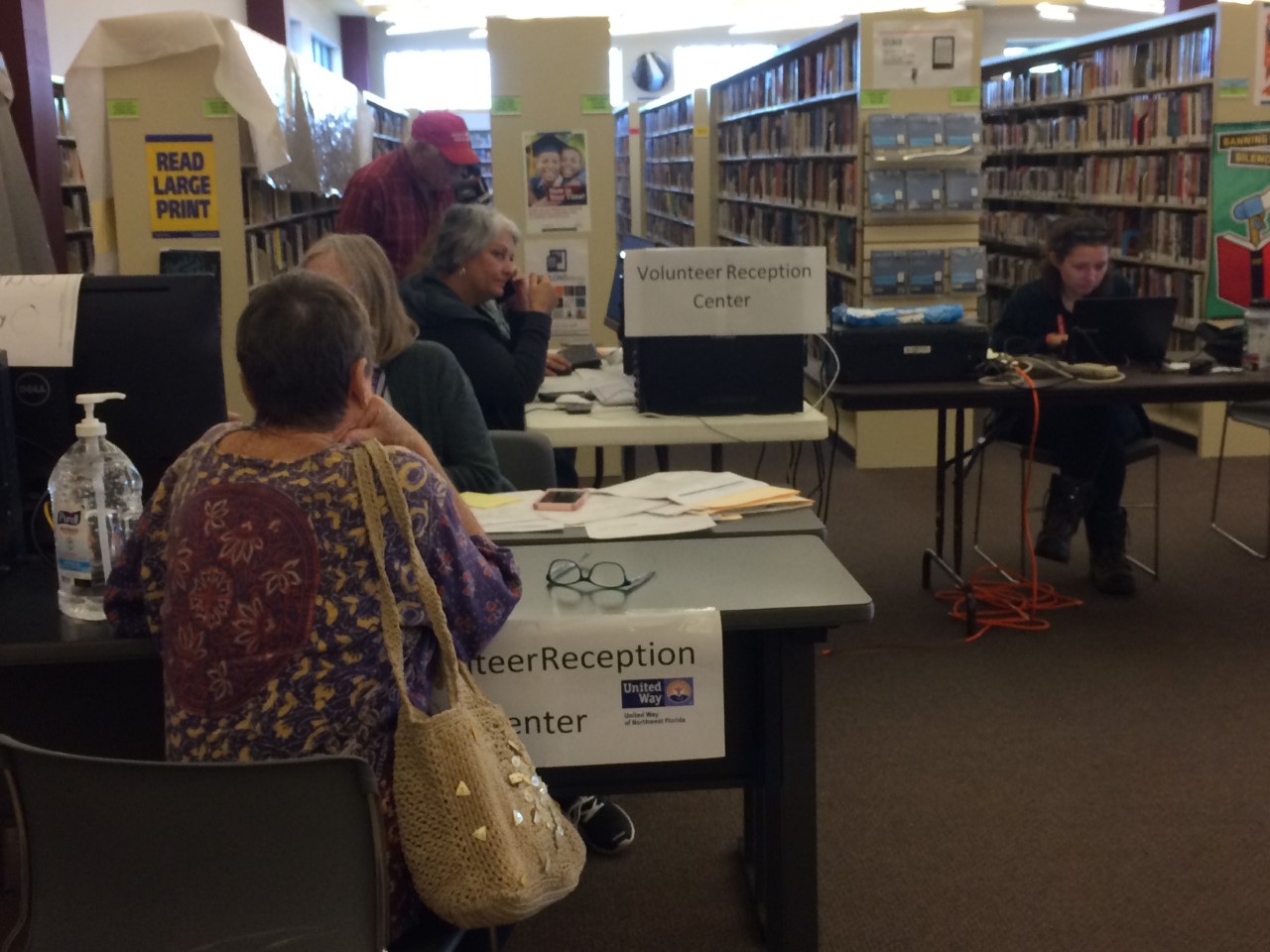

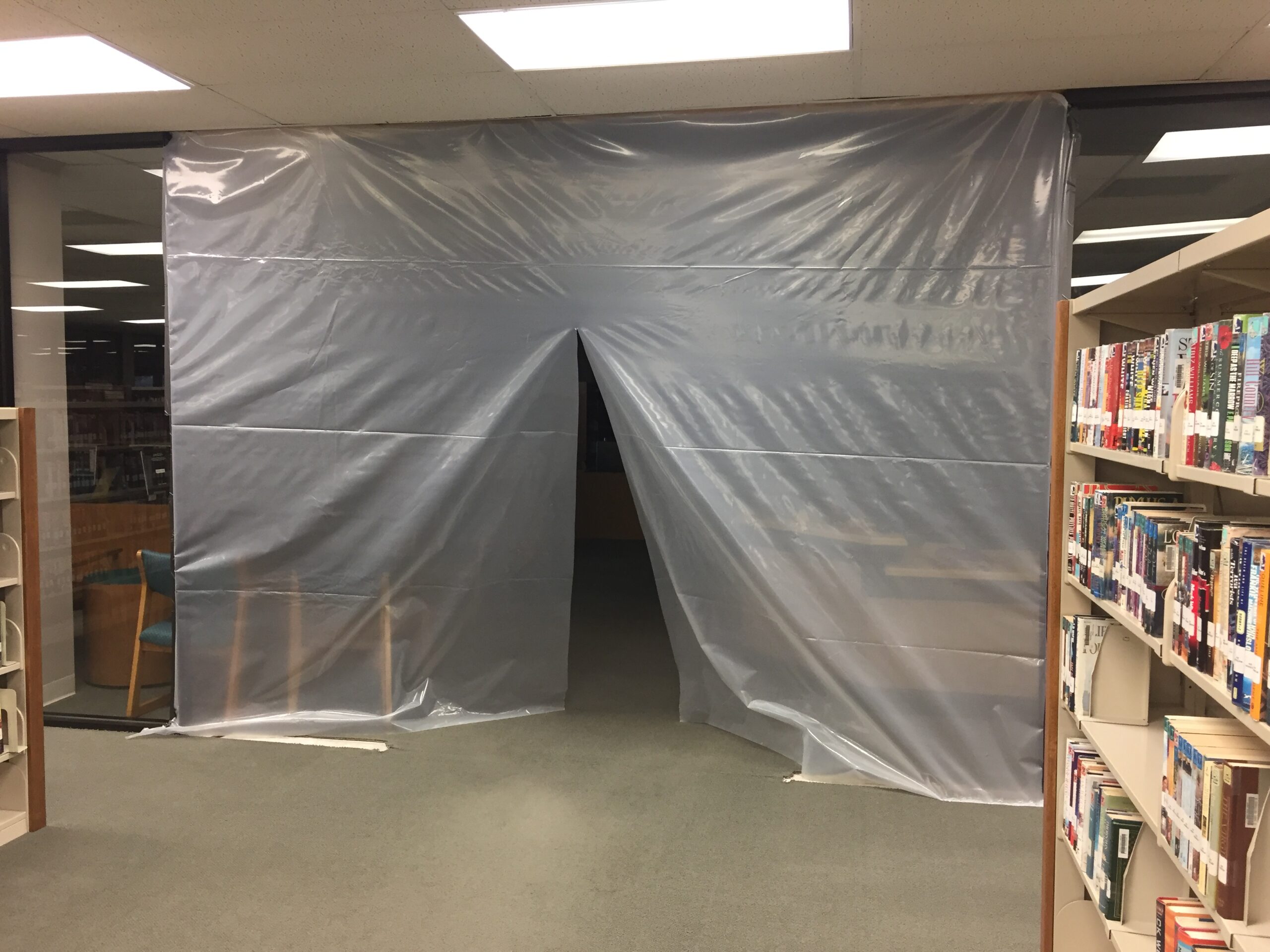

The libraries’ physical space may become repurposed after disasters in order to help communities distribute food and other resources, or even to house and support volunteers. The material infrastructure of the library interacts with its social qualities, enabling meeting rooms or computer access areas to become sites of FEMA filings, social worker visits, or even just temporary spots for physical respite from heat or insects or devastation.

Libraries’ and librarians’ roles as local knowledge infrastructures were sometimes ignored by aid organizations and local officials in favor of repurposing library space and library personnel as ‘emergency response’ resources. Their professional expertise in locating and assisting with finding resources should be underscored among governance structures (e.g., city and county officials).

Research Question 2

The communication practices libraries deploy to communicate with people are a key component of our research. Informing people generally is what libraries “do,” but special needs arise during disaster preparation and aftermath. The librarians primarily relied on word of mouth and phone calls in order to communicate, coordinate, and disseminate information to interact with various stakeholder groups, including community members, faith-based organizations, local official, and relief organizations. We found that some disaster relief workers were able to use librarians effectively, while others did not.

The strength of libraries during disaster recovery is their ability to coordinate disparate organizations, local government, and faith-based organizations and effectively leverage their local communication networks to provide assistance. Libraries’ electronic resources, including computers, Internet access, fax machines, and printers, become important to community members’ abilities to work with social service and insurance organizations. Word of mouth and simple texting and, especially, road signs – often regarded as low-tech tools – were often used by libraries to circulate disaster-related information, and especially recovery information.

While social media, particularly Facebook accounts, were acknowledged to be important for sharing recovery information, for medical and natural disasters, most libraries were poorly equipped to create and circulate their own content. Libraries that were part of a larger, usually county-wide, library system had more capacity to provide branch libraries with substantive social media content designed to keep the members of the county informed not only about library operations and offerings but also disaster information and resources, which reduced the burden on library branch managers to produce social media content. Similarly, State Library organizations provided significant support after disasters, and also functioned as helpful social media content providers; the latter was especially useful since few libraries created much original content regarding either COVID-19 or physical disasters. In Texas, one non-profit resource organization provided a great deal of trusted, useful information to local libraries by providing libraries with an email listserv to connect librarians in Texas.

Libraries also played a crucial role in connecting community members to the resources provided by faith-based organizations (FBOs). Small town and rural libraries frequently worked with FBOs in responding to immediate physical and emotional needs of the community. In particular, librarians noted that FBOs oftentimes provide unique resources, such as pet food and chainsaws, that were otherwise unavailable through disaster relief organizations. By coordinating the disparate resources in their communities, librarians uniquely provided streamlined information in the aftermath of disasters. The communication practices of libraries during disasters were highly responsive and librarians relied on their skills to coordinate and navigate complex and evolving situations.

Research Question 3

Resiliency is a key component of librarian response to disaster, and we identified five types of institutional practices that affect their own resiliency and that of their communities. First, the long-term approaches librarians adopt to counter disasters prepared them for subsequent problems; even as they repurposed themselves to respond and to aid in immediate recovery, many of their practices and training appear to help their communities recover in the long term. Second, recognizing that the library is a place to gather enables librarians to think through what communities might require in the next disaster, whether it is comfortable places in which people simply recover or information from social services or better collaboration with aid organizations. Similarly, when regional libraries have occasions to meet or work together, they build productive and supportive relationships that can pay benefits during disasters.

Third, as skilled information professionals, librarians clearly contributed to their communities’ resiliency; reinforcing that recognition of librarians’ expertise on the part of aid groups and on the part of local officials could enable libraries to have even more effective roles. Fourth, certain organizational structures contributed to libraries’ part in cultivating resiliency. For example, when library representatives are routinely included in disaster planning bodies, such as in counties or in regional groups, the efficacy of libraries improves. Clear communication and an understanding of needs and resources improve overall responsiveness of local institutions and contribute to community resiliency. Finally, the recognition that communities rely on a sense of identity from their histories as physical places with unique events and people builds resiliency and community. To foster identity, gathering and composing community narratives and storytelling can be a significant library function.

.

.

Conclusions

Planning for disasters is complex, and the range of actual disasters that libraries may face means that libraries “need something bigger” than a single plan for a single sort of disaster. Uncertainty, whether it entails the duration and seriousness of COVID or the length of time a hurricane could stay in a region, as Harvey did in Texas, suggests recasting responsiveness from an ‘emergency’ mindset (ephemeral or temporary) to a probability framework. As evidenced by the data collected throughout these interviews, the contribution of librarians to their communities during times of disaster is crucial and fills an unmet need for not only individuals in the community, but also local government and disaster relief organizations. Further, that librarians are “filling-in-the-gaps,” which means that these gaps are not systematically addressed by local disaster plans, and that librarians do not receive the necessary support to continue to do so, increases the likelihood and effects of burn out.

Subsequently, this research found that resiliency operates at two levels for libraries in small towns: (1) how librarians support and strengthen the community’s resiliency and (2) the resiliency of the library itself. Libraries support the resiliency of their communities in several ways. First, the informal support and ‘humanitarian spirit’ of librarians strengthens community resiliency. Many of the ways libraries contributed to their communities’ resiliency extended beyond their formal job duties. The ability to go where they are needed and that librarians are uniquely trusted in their communities meant that librarians were effective at providing the assistance their community needed. This community embeddedness helped to ensure the resiliency of their communities. Librarians are deeply embedded in the social fabric of their small towns by living in their communities, their personal relationships with people in the community, their interpersonal interactions with patrons at the library, and the library as a department of the local government. This places libraries in a unique role to connect people to each other, to organizations, and to local government. The nature of this embeddedness allows libraries to contribute more significantly to resiliency than many disaster relief organizations or government agencies. These close ties to their communities allowed librarians to act as intermediaries or bridges between disaster aid organizations and the people in need in their communities.

Further, the physical infrastructure of the library shaped local community resiliency. Libraries offered key meeting spaces during and after disasters and were often the only community organizations or spaces capable of meeting these needs. They offered patrons the ability to access necessary resources such as computers, wi-fi, and even cleaning materials after hurricanes. The diversity of physical resources available at the library is a unique resource for the community that cannot be found at any other building. Librarians, for years, have heard that the internet will make libraries obsolete, yet the evidence of this research demonstrates that the physical nature of the library building and its ability to provide internet access is more vital than ever for their communities. As one Calhoun County librarian stated, “the internet can’t provide free meals and cots and places during a storm.”

Besides the physicality of the library and its resources, libraries as social infrastructure is another important contribution of libraries to community resiliency. During and after disasters, libraries helped to foster civic life and maintain a sense of place in their communities. They operated as spaces for people to come together and socialize, as well as share common stories about their experiences during these times of disaster. This was most evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. Librarians shared how patrons missed the socialization available at the library. Being able to share in social life without the expectation of payment means that the library is a unique space for socializing, particularly in small towns.

Lastly, the responsiveness of librarians to community was important for community resiliency. Libraries were tasked with nimbly meeting the changing needs of their communities during and after disasters, and librarians often adapted their physical spaces, services, and programming based on what they observed within their communities. Libraries with established communication avenues with their patrons were more effectively able to respond during disasters and keep their patrons up to speed.

Taken together, these factors of community resiliency that the library cultivated are a unique contribution of libraries that should be acknowledged, celebrated, and incorporated into disaster mitigation and planning efforts at the local level and supported at the state level. Yet ensuring the resiliency of the community is only possible if the library itself is resilient. Libraries that had adequate resources thrived and weathered disasters more effectively than libraries without similar forms of support. Support for library resiliency came from their local government, from a countywide library system, from informal relationships with other libraries, and from state library organizations. The libraries’ ability to adapt was equally crucial for the resiliency of the library as it was for the resiliency of the community. Librarians quickly pivoted their roles to serve their communities. They proactively protected libraries’ physical resources from damage and worked to quickly reopen – both physically and digitally – after disasters and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The librarians interviewed for this project faced many challenges that threatened their resiliency. From personal tragedies resulting from a disaster, to apathetic government workers, to cultural resistance to preventative measures, the resiliency of librarians is even more striking in the face of these challenges. Many of the librarians regretted their lack of formal disaster training and wished they were more able to prepare in the event of disasters. Although most of the librarians had experience from previous disasters, the lack of formalized training for librarians specifically to plan, respond, and recover from disasters meant that many of the librarians were making it up as they went along and filling in gaps themselves.

To support community resiliency, libraries need to be recognized by their local governments and systematically incorporated into disaster mitigation plans. That training would enable librarians to respond even more efficiently to disasters, like chemical plant explosions and COVID-19, that offer no time to prepare, as well as disasters, like hurricanes, that come with some forewarning. Training should also go hand-in-hand with mental support resources for librarians. By fulfilling a coordinating role and by working directly with community members, librarians need support in order to continue supporting their communities. The resiliency of librarians is crucial to the resiliency of the library, which is vital to the resiliency of the community as disasters have become a way of life.

IMLS Log Number: RE-96-18-0127-18; Laura Bush 21st Century Librarian Program

The Researchers

Sharon Strover (Principal Investigator)

Marcia Mardis (Principal Invesitgator)

Richelle Crotty

Srivalli Dorasetty

Denise Gomez

Zoe Leonarczyk

Cameron Lindsey

Martin Riedl

Emily Rubin

Curtis Tenney

Presentations

Co-Constructing Disaster Response: Researchers and Practitioners Collaborating for Resilience in Small and Rural Libraries

Marcia Mardis – Associate Professor, College of Communication & Information at Florida State University

Sharon Strover – Professor, University of Texas at Austin

Faye Jones – Professor, Florida State University

Researchers from Florida and Texas reported their experiences co-constructing narratives of disaster planning, response, and recovery in the wake of the last 5 years’ regional hurricanes. This session, rich in verbatim data, photos, and other documentation, detailed the process that researchers used to engage as partners in understanding disaster experiences and critically evaluating public librarians’ roles in community resiliency. The session also included opportunities for audience members to share their own experiences through storytelling and discussion.

To download the presentation, click here.

The American Library Association (ALA) is the oldest and largest library association in the world. Founded on October 6, 1876 during the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the mission of ALA is “to provide leadership for the development, promotion and improvement of library and information services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and ensure access to information for all.”

Contact us

The Technolgy & Information Policy Institute main office is in the Jesse H. Jones Communication Center, Building A. We are part of the Moody College of Communication.

Find Us

2504 Whitis Ave.

CMA 5.102

Austin, TX 78712

Phone

512-471-5826

Social

Twitter: @texastipi

Facebook: @texastipi